Books that capture my heart in a specific, unforgettable way become subject to my Book Hour feature: long-form reviews that sit with the details and often veer into the personal. I always avoid explicit spoilers, but cite from the book freely and reference significant scenes.

Knowledge is power, the adage goes. But what if you are born into a world without knowledge, without culture, without history? What if there is nothing for you to learn?

This is the case for the narrator in Jacqueline Harpman’s 1990 novel I Who Have Never Known Men, translated from the French. It follows a young girl who, along with 39 other women, lives in an underground cage manned by unspeaking male guards. The women do not know how they got there, nor the reason for their entrapment, though they have vague memories of a previous life. The girl, however, knows only the cage. Unlike the women, who are resigned to their situation, the girl is curious about what lies beyond it. This makes her a pariah, but it also makes her the key to their escape.

The novel is an astounding piece of fiction that asks what lies at the bottom of our humanity when we are removed from everything that makes a life worth living: love, culture, hope, knowledge. It is not, to me, a particularly probing novel; it keeps its head bowed in the face of enigma. The prose is clean. The images veer from visceral and distressing to removed and beautiful. The book’s refusal to give answers or explanations is what makes it so compelling. Like the girl, you are curious. This is what I think all great fiction does: spark curiosity, which is one of the greatest pleasures of having a mind.

When I say curious, I don’t mean just about the reason for the women’s imprisonment. That’s where the curiosity begins, but any book can summon that with a strong enough hook. And in a book where knowledge itself is a precious rarity, you’d be a fool to hold out for a neat explanation.

No, your curiosity quickly drifts from the novel’s big unknown towards the astonishing and idiosyncratic smaller ones: the unfamiliarity of fantasy in the mind of a girl who has never known affection. What a stranger might feel if you refused to break eye contact with them. How to tell time when there are no clocks. All of these are acts of extreme imagination for the girl, but by thinking them through, she achieves a sense of satisfaction, she discovers her humanity.

One of the first instances of imagination the girl exercises is in trying to imagine the appeal of sex, which the women discuss occasionally. She begs the women to tell her more, but they see no use in it.

“After a few sighs, she came out with the usual reply:

‘What point is there in your knowing, since it can’t happen to you?’

‘Because I want to know!’ I raged, suddenly grasping why it was so important to me.”

This want, this curiosity, is annoying for the women, but unbearable to the girl. Without an answer, she retreats into her brain, engineering imaginary scenarios with a male guard. Her imaginations are based on acts of interrogation, which the women have described the guards engaging in. It’s sexless but exciting and leads her to her first orgasm (though she doesn’t know that’s what it is). “After that,” she writes, “my mood changed. I no longer tried to persuade the women to tell me their secrets; I had my own.”

Through the act of imagination, the girl turns automated days into opportunities for meaning-making. She storytells different scenarios about the guard, she counts her heartbeat to measure time. In other words, she turns existence into experience. It is thrilling to encounter on the page—the basic but brilliant act of the mind at work, creating something out of nothing.

I no longer tried to persuade the women to tell me their secrets; I had my own.

What makes a person curious? Is curiosity innate? Is it taught? Why is it that some people “prefer not to know” while other people cannot bear being in the dark? Most children are curious because they know nothing, but I’d argue that most adults know next to nothing still, so why aren’t we more curious? When we discover answers to our questions, does that make us feel a little better about having asked the question in the first place, a little safer in our own mind? Is curiosity dangerous? I mean, it did kill the cat, but didn’t satisfaction bring it back?

I fear the deterioration of my own curiosity. In the same way that friendship groups winnow and our taste in music stagnates as we grow older, I worry about being placated by my own tastes. In the past year I wondered if I could call myself a curious person. I do make efforts to stretch my intellectual curiosity. But I feel less confident in my social curiosity, which I am also more reluctant to challenge. I gravitate towards people who are similar to me, whether in interests or emotional intensity or communication style. When I sense friction in a friendship, my instinct is to concede or back down until it passes, for better or worse.

Put generally, I orient towards emotional harmony and safety in my friendships. Other people may orient towards curiosity (this person is interesting, what can I learn?) or passion ( this person makes life more fun and exciting) or utility (what can this person do for me, what can I do for them?) or something else. Of course these factors can show up in every friendship, and I have very cherished friends of different kinds, but I’m far more inclined to pursue a friendship with someone I feel a thrilling familiarity with—it feels like we’ve known each other our whole lives!— than someone who I find fascinating but distant. (Maybe this is how most people feel, but someone did tell me recently that they are attracted to people who are very different from them, and I have been thinking about that since.)

The ability to discover new perspectives or ask probing questions can be a privilege. Your experiences in the world inform how willing you are to open up to or trust the unfamiliar. This is certainly true for the women in the cage, who have long forgotten their past lives and are unwilling to dredge up memories of their families. It’s far too painful, even the girl can see that. And most of them worked household or service jobs, accustomed already to a life of curtailed agency. The specific combination of life experiences and trauma have numbed these women’s ability and appetite to question their situation.

Because the girl lacks these life experiences, the trauma of capture fails to obliterate her autonomy. Her privilege is that she is young. Unlike the women for whom their selfhoods have been snatched away, hers is yet to form. That’s an opportunity.

Curiosity has no price for her, it does not dredge up painful memories or force her to confront the limits of her intellect. No, curiosity is her tool for survival, and it soon becomes its own reward.

In most dystopian or post-apocalyptic fiction, scarcity plays an animating role. The lack of food or shelter pressures the characters to act or perish, driving the paranoia and unrest that erupts into violence (à la Lord of the Flies). Hunger and danger: without the two, there’s hardly a challenge, is there?

The lack of danger in I Who Have Never Known Men is, ironically, one of its most unsettling forces. The women have all the food and shelter they need, but they are entirely alone. This book trades the daunting question of survival for a far more horrific mental task. What do you do when surviving is easy, but living is unbearable? What meaning do we make for ourselves when there is none to be found?

Some of the women become couples or threesomes. They work together to build houses and recuperate food from a seemingly endless stash. They communicate openly and freely, always giving thanks and appreciation. Despite being removed from culture, it’s clear they begin to create their own. But for the girl, any hope of true meaning or satisfaction lies, as ever, in the recesses of her own brain.

“After our escape, Dorothy used to say: ‘Let’s organise our life, let’s not waste our thoughts.’ The fact was, I could use my thoughts as I pleased, the idea of wasting them was absurd. My survival was guaranteed… I could allow my mind to wander as it pleased.” (150-151)

Allowing the mind to wander—what a joy! I love this frank and utilitarian perspective on daydreaming, on letting one thought branch into two or three, subconsciously picking the path you want to take, following it as it changes in a flash to something else, all of it aimless but none of it useless.

The girl rarely feels the satisfaction of company, friendship, or touch. But she feels the pull of her own mind, she excites herself with ideas of expeditions, she replays over and over again the same rhetorical questions: why are they here? What happened? Where did the guards go?

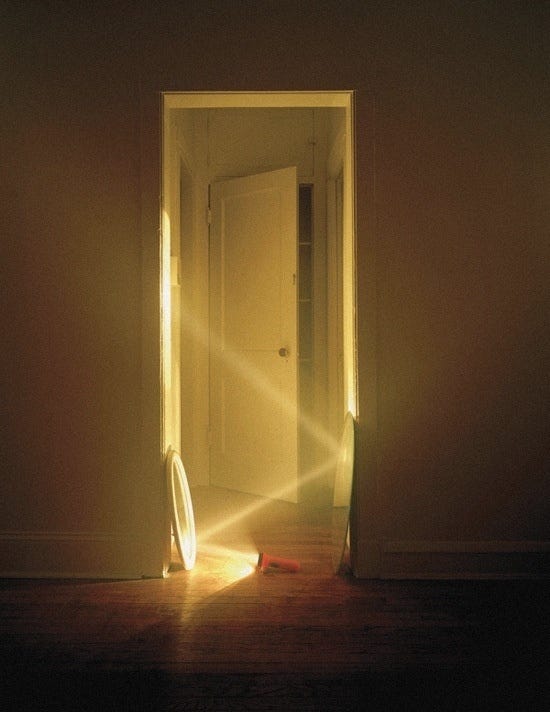

Her questions mostly do not bear answers. But even a moot question has potential to conjure a new idea. When this happens to the girl, it’s one of my favorite moments in the book. When pondering the guards that used to man the prison, she suddenly arrives at a brand new thought:

“These words kept haunting me and were beginning to annoy me, when at last an idea began to form…what if [the guards] were as much in the dark as we were? I was electrified by this theory, I could feel my footsteps dancing and I began to laugh. I was perfectly aware that I had only added another question to all the others, but it was a new one, and, in the absurd world in which I lived, and still live, that was happiness.” (151)

It takes decades for her to arrive at this idea, but the thrill of the novelty lasts her days. It makes the wondering worthwhile.

“[It] was a new idea, and to me nothing seemed more precious.”

Nothing is more precious than a new idea. The book seems to offer that thinking and sense-making is humanity’s most original and gratifying instrument. You can be completely alone in the world, you can have nobody to talk to or understand you, but you can still think, you can still wonder, and that’s something.

When the book was first translated into English, it was called The Mistress of Silence, referencing a phrase towards the end of the novel. In 2018, it was reissued as I Who Have Never Known Men, a more direct translation of the French title, Moi qui n’ai pas connu les hommes. Needless to say, this is a far better title—immediately intriguing, personal yet distanced, strange. But I also love it because I think the tension between knowing or not knowing, of building from nothing an understanding, lies at the very core of the book. The girl’s not having known men sparks her first act of curiosity. This curiosity is a privilege and a pleasure that remains with her, and with you, the reader, animating a life of total lack, until the very end.

I am almost finished this book and wow, your review is spot on so far ☺️🙌🏼

Can’t wait to read more from you!!

i cannot wait for you to write more book reviews because this was so brilliant