I met Maryse Condé, one of France’s most honored postcolonial writers, when I was twenty-one years old and studying abroad in Paris. At the time I both clung onto her every word, awestruck by being in the same room as a writer, and failed to fully grasp the immensity of the privilege. She came to speak for a course I was taking on post-colonial Franco-African culture and literature. Either due to my insecurity with the French language, the five years that have since lapsed, or a then-intense preoccupation with where my life was headed which, with only a year left until graduation, obsessed my every thought, I cannot remember a single thing she said about postcolonial French literature. But I do remember one thing. It anguished me, I wrote it down. When asked about the act of writing, she said that you must think of the person you are writing for, and write for them. That’s all that matters.

For all the reasons listed above, on top of the sad fact that I cannot actually find the notebook I used for this class, I may be misremembering. I am likely stripping from her words the context of her oeuvre, which, as among the most seminal works of Caribbean literature by a Black woman in France, necessitated demanding an audience. I may be using Maryse Condé (!) as a mouthpiece for my own anxieties.

Still, whatever her words, the message felt clear and important to me then, as someone who desperately wanted to be a writer but had no idea how. And the memory still feels real to me now, five years later, as I finish another round of revisions for my debut novel. It awakened something in me, a snag, simultaneously an exacting direction for how and why we write (the answer I was looking for) and a troubling omen (the answer I did not want), because I overwhelmingly felt that I did not have anyone to write for. In fact, it went beyond that, I didn’t want to write for an audience, I wanted only to write for myself.

There’s much to say on the subject. Other people with more authority on the matter can speak about it better than I can. I haven’t put a book out, I still hesitate to call myself a writer. But I write, and because I write I feel things about the act of writing, and the question of an audience, the reader, has lingered in the background of the act of my writing for half a decade, and so I am writing this now to see if I can figure it out. I suspect I won’t, and I know my thoughts may change in the future. But, right now, this is how I feel.

Writing is an individual act. It comes, unbidden or extracted with great effort, from the private rooms of your mind, rooms which other people cannot know or enter though, if you’d like, you can get them to try. I guess that’s the act of putting words on paper. It’s an invitation. You hope the reader will accept.

But do we write so that the reader will accept? Should I be writing the key to the room, or the room itself? Throughout the writing of my novel, I have tried to write the room. Because I dislike self-consciousness in books, I have been careful to not think of the reader, to push them away when I feel them creeping behind a sentence (will they understand this? Do I doubt their judgment?), or dragging down an idea (this is strange—they’ll think it’s perverse—is it?).

This is the snag. Of course, our brand-obsessed world nurtures these anxieties. So often the author is made to be an easily digestible public persona, detached from the private, complex imagination from which a work is produced. And public personas subsist on audience capture, collective understanding. I suspect this encourages the self-consciousness that pops up so often in contemporary prose. It’s hard not to think of audience when the size of your audience often determines your success, at least as it relates to a paycheck. Still, should we be writing to satisfy their tastes before the work itself knows what it wants to be? What even are those tastes, can anyone indulge them successfully without being caught?

It’s fairly easy to tell when the author knows—and, more importantly, wants you to know they know—the specific reaction their work may elicit. An example is when a perfectly interesting character happens to also be potentially offensive (against general contemporary standards, which, it should be noted, shift constantly) and the author turns them into a joke (“I think they’re pathetic, too!”). Even worse is when the author thinks they’re getting away with it. When they know they can make you cry, for example, and do it without intention or control (I feel this way about Hanya Yanigihara’s A Little Life), so that you suspect the entire novel has been constructed not for its characters to be carefully challenged and gratifyingly changed, but rather for you, the reader, to weep.

It’s difficult to separate an author’s intention from the reader’s experience. Perhaps in a particular author’s private room, that character really is just pathetic, or Yanigihara’s Jude must bear the traumas of the world to achieve her goal of the book. I guess that’s why it’s useless, as a writer, to try to marry them. To write for anyone is to write for noone. To cater to an audience is really to cater to your own anxieties, the reader you made up in your head. They don’t exist until they do, and by that time, the work’s done, it’s too late. I have been trying to remember this.

But I love the reader, even the imaginary one. Love isn’t the right word. Sometimes I resent them. Other times I look to them for help. All the time I try to ignore them, but they are still there. Condé’s words still echo in my mind. Maybe what I mean, then, is that I recognize them. The question is what to do with that.

In Gabrielle Zevin’s Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, Sadie and Sam are video game designers whose friendship takes us through decades of ideation, creation, success, and tragedy. It is a story about artistic partnership. It is a story about art. I enjoyed it particularly for what it says about the act of creating. Early on in the novel, as they work on their first game together, Sadie says to Sam: “To make a game is to imagine the person playing it.” I underlined that. I thought of Maryse Condé. It’s a beautiful sentiment. Creation for the sake of an invisible other, unknowable in every way except the most important, which is the fact of shared creative play, experiencing for a while the colors of a room in someone’s mind, impenetrable most of the time but, for a moment, made open for your pleasure. The work as the key, then.

“To make a game is to imagine the person playing it.”

But is to write a novel to imagine the person reading it? I’m not sure. Something in me resists this parallel. Like anybody, I want my work to have an audience. But do I want, primarily, to be read?

What I want is to create something that satisfies my expectations. Expectations of truth, of quality, of style, who knows, but they exist, and they’re mine. Even while writing this, I mostly just want to figure something out, this snag of mine. I want the novel to be mine too in this way, a private thing that just so happens to, when it’s ready, come out and be known, but the way that it is known is none of my business. (I’m aware I’ll feel differently if and when the book does come out, but right now I can’t imagine it).

I was excited when, years after the semester I met Condé and committed to making for myself a future in books (I got my first publishing internship that summer), I came upon a fragment of an interview with Elena Ferrante in The Paris Review. Ferrante is one of my favorite writers, her Neapolitan Novels to me testament to fiction’s greatest powers. But sometimes it’s hard to read her work, especially her essays and interviews on writing. They inspire me, they give me pain. It feels like she’s offering something like an answer but I’m scared I can’t use it, I’m just not that good. (Most of my favorite writers do this to me, it’s why I love them.) In the interview, she posits that “Literature that indulges the tastes of the reader is a degraded literature. My goal is to disappoint the usual expectations and inspire new ones.”

I have passively assimilated from many sources the importance of not catering to an imagined reader. But because Ferrante occupies such an outsized place in my psyche, hers was the first challenge powerful enough to counter the equally outsized sentiment I attributed to Maryse Condé in my formative years. Not just permission, but an imperative to forget the audience. The consequence of not doing so, but also the possibilities on the other side. My understanding of literature, which is always changing, gaining a new edge.

The question of who I want to write for (nobody?) and who I am, in practice, writing for (the stranger who might come to experience my room and understand it in their own particular alchemic way?) lingers with me, easy to forget but difficult to be rid of, like the background hum of cars passing below the window of my flat. Writers I love and admire (such as Ferrante) champion a total private attunement to the self when it comes to the work. I’m inclined to agree. But the impulse to think of the imaginary reader, though checked by my own instinct of self-betrayal, is still coaxed by my belief in the reader’s incontestable power, as Sadie impresses to Sam, to breathe life into a work if the work is good enough to hold them. I want to bring something into the world that I feel is faithful to my own sensibilities and achieves the ambitions that are so personal to me. But I also want to bring something into the world. What is the world, in this circumstance, if not an audience?

“Literature that indulges the tastes of the reader is a degraded literature.”

I have a confession to make. All this time I’ve been conjuring a specific version of the reader, someone I don’t know, someone demographically similar to me, maybe, in their mid-twenties. Early twenties, even, the age of my protagonist. Curious about reading, but without particularly strong opinions on how books should be.

But there’s another reader I have in mind. I’m embarrassed to say. You already know them. It’s Maryse Condé. It’s Elena Ferrante. It’s every writer I have read and admired. That’s another reason for the snag. Even though I may have put my foot down and waved the unnamed reader away from my manuscript, the writers I know and love still hover over it. I wonder how they’ll feel. I wish for my work to be good enough. It’s self-indulgent. Bad for the writing. I try to push them away, too, but it’s harder because I feel they know something I don’t, and I want to learn. Instinct and self-trust are built with time, and I’m still building mine. That’s the reason I’m writing this at all. I have to trust that if I write the room well enough, there won’t be need for a key.

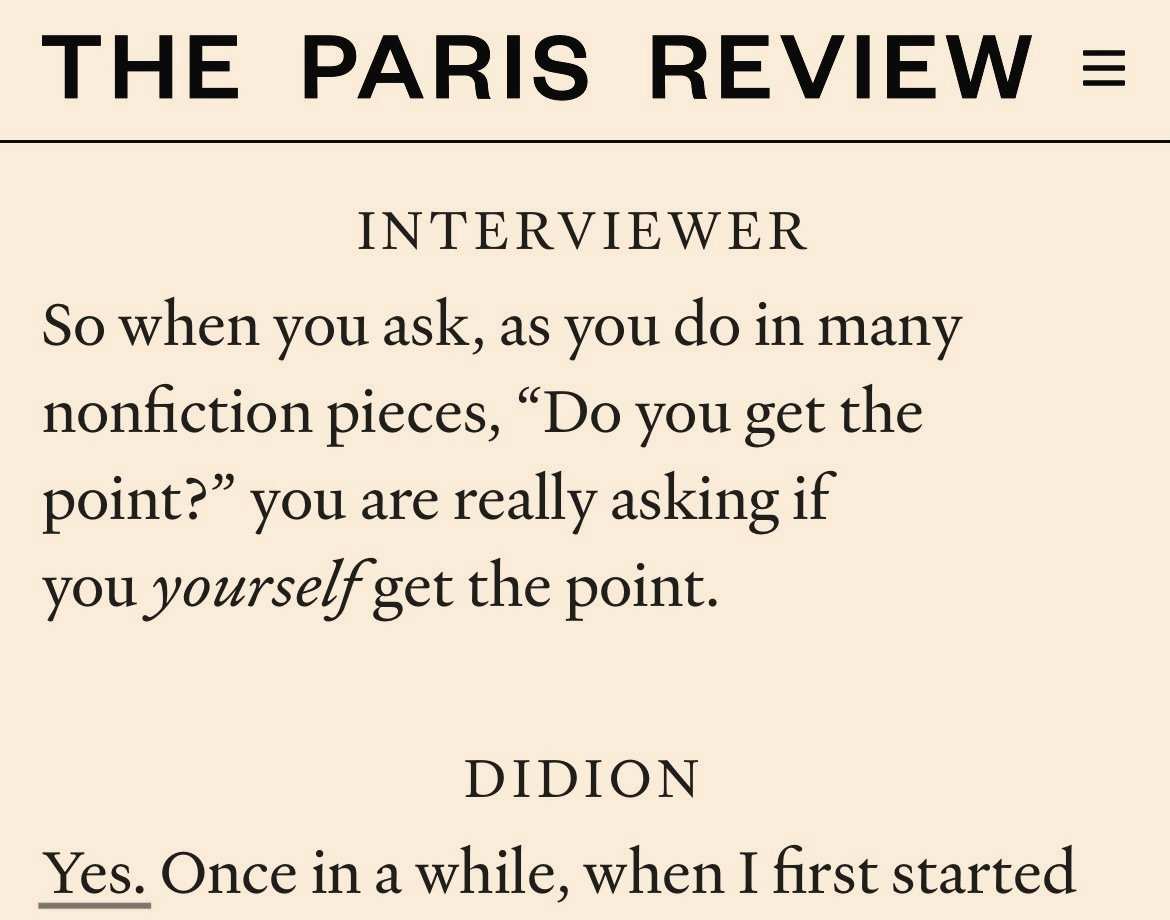

Joan Didion once described the act of writing as hostile—“hostile in that you’re trying to make somebody see something the way you see it, trying to impose your idea, your picture.” I see it as hostile in another way, in that you’re trying also to erase the reader, push them away, banish them from the margins until you’re finally ready to open your arms, receive them. Really, it’s hostile all around.

It’s a good interview. And it also offered something in relation to this long-standing mental “Condé-Ferrante” paradigm of mine. The interviewer, Linda Kuehl, asks Didion whether she’s conscious of the reader as she writes. “Do you write listening to the reader listening to you?” Kuehl asks, putting the feeling of the snag into words.

“Obviously I listen to a reader, but the only reader I hear is me.” Didion says. “I am always writing to myself. So very possibly I’m committing an aggressive and hostile act toward myself.”

If I am to take my memory of Maryse Condé’s words as truth, will you allow me to remind of them again? You must write for a reader, she said. I do. There’s another reader I know. It’s me.

Thank you for reading the first post of Blue Hour! For more on what I read and write, subscribe for free.

Book: I’m currently reading The Great Believers by Rebecca Makkai. It’s good, I’m taking my time with it.

Song: Recently I’ve been overplaying “Time Comes in Roses” by Bess Atwell. I discovered it back when I was writing the first draft of my novel, and it captured a particular sentiment I was focused on at the time, the realization that time passes and you continue to be the person you are. It’s tricky to communicate without sounding sentimental or navel-gazey. In a song it works, the line is: “Nobody thinks I’m special yet.”

Thought: This year, I broke three wine glasses. I only have one left. I’m going to IKEA this afternoon to buy another set. Going to IKEA is such a treat that I realize I’ve been putting off replacing the previously broken glasses to save myself the pleasure of doing so, the way you avoid sticking a sticker because the moment you finally do is both wonderful and also kind of devastating since you have no idea when you’ll next stick something. Or like those kids in the marshmallow test who held off on eating one marshmallow in exchange for two. Ever since I learned about that stupid test, I’ve been holding off on eating my marshmallows.

Stacey, I don't know if you over-deliberate when writing (I'm sure we all do...maybe) but I must say, your writing is so natural. There's such a good cadence to it. I can't wait for the day your debut novel is unveiled and will happily take the place of that imaginary reader (and/or yourself). Thank you for sharing your thoughts and words!! Feeling very grateful I get to witness your writing.

i remember reading ferrante’s words for the first time and thinking how unbelievably cool it was to appreciate a distance between the writing and the audience!! i also love the idea that you, as the writer, are also a reader, and in experiencing your own words just as much as the audience does, you have the right to serve yourself through your art. this was fantastic <3