I recently discovered what a rolodex is. I learned about it through an NBC article from 2010 called “The life and death of the rolodex,” one of the top Google results for “rolodex,” which I looked up after reading this Rayne Fisher-Quann letter. In it, she gives advice about resisting digital over-consumption, one of them being writing down recipes on cards and storing them on a rolodex.

For years I assumed I knew what a rolodex was, because they occasionally popped up in books set in the 80’s or 90’s. Context clues led me to believe it was something like a phonebook. Subconsciously, though, I assigned it the spirit of a Rolex. If you made me sketch it out, I probably would’ve drawn some kind of paperback with the girth of a fat wrist. (If you don’t know what a rolodex is, it’s “a rotating card file device used to store a contact list.” —Wikipedia)

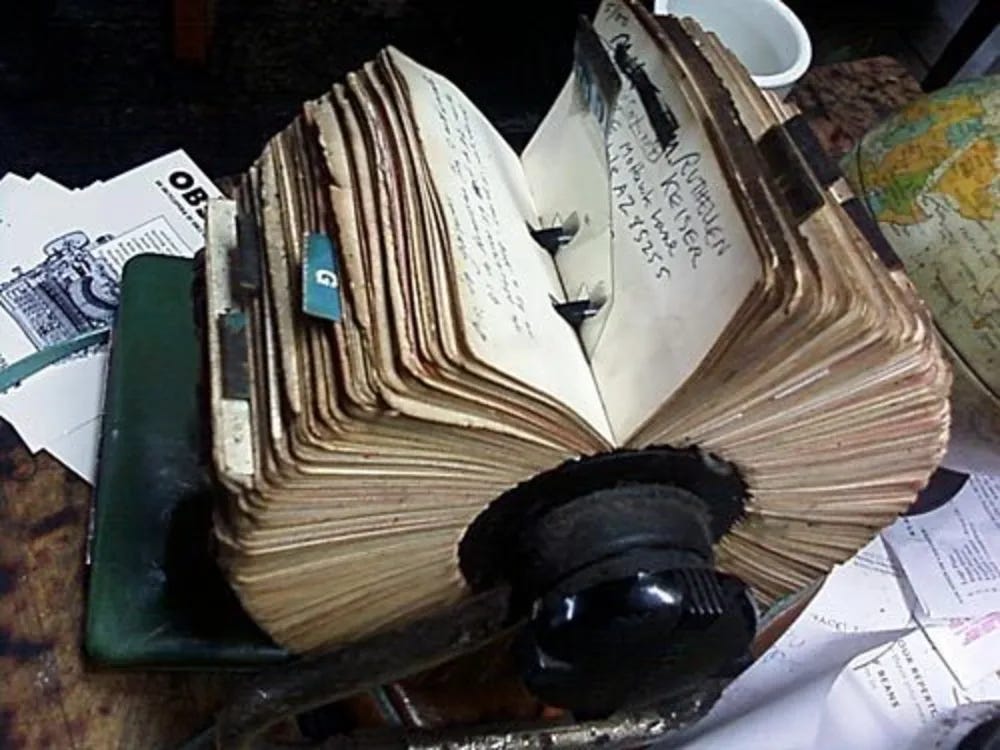

I was shocked to see its true shape and form. I admit the picture provided in the NBC article was weirdly zoomed in, eliminating any sense of scale, the pages stiff and moldy-looking. It was strange beyond my wildest expectation. It reminded me of a mouth with too many teeth, none of them functional. I’m not exaggerating when I say it repulsed me. I also felt humbled, confronted with the truth that time really does pass, and objects, not just animals, go extinct. You might think this is obvious, but you can go your whole life knowing something logically but not emotionally.

So I became emotional about the rolodex. How sad for something that was once so ubiquitous, so essential—hailed as “one of the more important memory systems ever created” (NBC, “The life and death of the rolodex”)—to be reduced to an idiosyncrasy. It sounds stupid, but I guess people really meant it when they said the Internet changed everything.

One big change, I think, is that it phased out ugliness. I attribute part of this to Apple, whose obsession with minimalism and sleek visual branding ushered us into our current digital age. I think of the rolodex showing up to a house party attended exclusively by iPhones and Macbooks. And then I think of jumping in front of the rolodex, saying, Anybody who has a problem with him has to go through me first!, even though just a few moments ago, I was crashing out over how dumpy he is. (A later Google search produced sleeker, simpler rolodexes, but I bet those ones would still get side-eyed at the party).

Yesterday, while watching Gilmore Girls (season 4, episode 18), I was pleased to see my indignation over the death of the rolodex reflected onscreen. Over dinner, Lorelai goes on a passionate tangent about anvils. “Where did all the anvils go?” she asks. She becomes increasingly distressed. “Everyone had them. They were featured prominently in every movie western, so where did they all go?… I mean, is there some secret anvil storage facility the government is keeping from us?”

I didn’t know what an anvil looked like, either, so I looked it up. It’s just a pointy block of metal, kind of like a brutalist interpretation of a shark. This is not so scary. I can picture it in a museum, in the tools and objects section, showing how we lived in the olden days. I can even picture it in some rich person’s home. There’s a simple purity to it, like it has always existed1.

The rolodex, on the other hand, lacks the anvil’s sense of primordiality. One look at it and you think, somebody with glasses and a high sense of personal agency—probably a Virgo—made you. I think that’s why it makes me so sad. Somebody made it, it was once useful, and now it no longer is.

I love objects. I don’t mean this in a materialistic sense, but pathologically. I attach feelings to the inanimate and conduct intimate dramas in my head about our relationships.

As a child, I refrained from touching items in stores because doing so would give them the hope of being bought, which, as a person with no money, was a hope I could not guarantee fulfilling.

I motivated myself to finish my meals by imagining that all food dreamed of going to “Tummyland” (this was also how I got around the perverseness of eating already alive-looking food, like Goldfish crackers).

When it’s raining and not too windy out, I still reach for my red duck-shaped umbrella Eloise, even though one of her ribs is broken, because I don’t want to deprive her of the joy of getting wet, which is an umbrella’s destiny.

I worry about what my stuffed animals will do for company after I die.

Sometimes I think there’s something wrong with me. I read “baby shoes, never worn” and feel sad for the shoes. I feel the need to clarify that I recognize the tragedy is that the baby died, but also, I feel sad for the shoes. Who will ever buy them? Where are they now? Where do objects go when they die???? (I know about landfills, don’t remind me.)

My tendency to over-animate seems to me a projection of helplessness—or, on the flip side, a grasp towards power. I believe I, like some frivolous and too-soft god, have the ability to change these objects’ lives. Rescue them from loneliness, or the feeling of being unwanted, or the disappointment of a boring life. Sometimes I worry that this way of thinking is just a by-product of consumerism, where the act of possessing is made to look like an act of self-actualization.

But no, I don’t think it’s that. My love for objects began before I knew about money. It extends beyond the point of ownership. I love objects that will never belong to me, like other people’s doors (are they being opened enough? Maybe they don’t care. Does being open feel good to a door? Maybe not as good as staying closed). A wooden chair with the armrests worn down. My neighbor’s bicycle, whose seat is always wrapped in a plastic bag to protect from the rain, like a shower cap. Why do I love things so much? Is this how hoarders feel?

A few years ago, a friend showed me the podcast “Everything is Alive,” an “interview show in which all the subjects are inanimate objects. In each episode, a different thing tells us its life story.” The first episode is about a can of cola, Louis, who dreams of being drunk by somebody, but is also terrified of it because he has no idea what will happen when he is empty of liquid. In other words, the episode is about a can of cola with a death drive.

I listened to two episodes. They were delightful, but I began to feel a bit weird about it. To me, giving inanimate objects the voice of a person, the name of a person, plus the ability to speak English defiled their objectness. I don’t think something has to gesture at humanness for us to love them2.

It’s becoming clear to me that this entire essay is about the fact that I don’t want to die. I know an essay about death is probably not what you signed up for, but honestly, I didn’t know this was what it was going to be about. Though, in hindsight, “The life and death of the rolodex” should’ve tipped me off.

I don’t want to die, so I don’t want anything else to die. When I love something, I wish for them to live forever. I know that chasing forever is foolish. Also, forever plays favorites. You can’t be alive forever, but you can be dead forever. That really annoys me.

Even though rationally, I know it isn’t true, emotionally, death feels like the worst thing that could possibly happen to someone/thing. And in my view of object-life, I hold onto a narrow logic, which was affirmed by the NBC eulogy: to be useful is to live. To be obsolete is to die. Thank you, late-stage capitalism.

But surely if objects are alive, they live in a way I can’t fathom. Holding them to my worldview would be like judging a hamster for eating its babies, which sometimes they do in the wild. It would be like going, that hamster is such a bad mother! Well, the human mind cannot comprehend the hamster one. The hamster is a hamster. The rolodex is a rolodex.

After closing all my rolodex tabs, I had to go to a meeting for work. I used to resent my job’s three-day in-office requirement, but now I don’t mind so much. Time passes. I work. Occasionally I experience an emotional revelation. I go home.

Around a year ago, for some unknown reason, my perception of time shifted so that I no longer saw the present as following the past, but rather as something preceding the future. This made getting through everyday annoyances easier, because I could see more clearly that the thing I did not want to do would not last forever, that there was a version of me that had already finished it.

It has also made birthdays slightly less tinged with doom. I don’t see myself as the oldest I’ve ever been, but the youngest I’ll ever be. (Ideally I’d be detached from any age-related anxiety, but let’s be realistic.) I think about the present through the lens of what is yet to happen, what we’ve yet to create or destroy. Right now is just a moment in time, waiting to be studied and then forgotten by people I will never know.

Maybe this is why the rolodex’s eulogy made me so distraught. I looked at my work-issued Macbook Pro and thought: you too may one day terrify a twenty-six-year-old.

Thank you for reading this week’s hour. If you also feel bad for inanimate objects as an adult, let me know. But I mostly assume that everyone feels this way, so if you don’t, feel free to let me know, too.

P.S. I looked this up after writing and editing this, I PROMISE—but the creator of the rolodex, Arnold Neustadter, actually IS a Virgo. I screamed out loud when I found out. I was so close to deleting that joke, because astrology jokes are honestly kind of trite/self-indulgent to me, but I guess instead I’ll be re-downloading Co-Star.

It has! It’s one of the symbols of the Greek God Hephaestus.

I don’t mean to criticize this podcast. I think, as I said, it’s a delight. But because I take objects far too seriously, in my heart this is how I feel.

This is how I feel about every item I’ve ever been given. I feel so emotionally tied to them even if I don’t particularly like the object itself

we love an anthropomorphizing queen 🖤 from someone who mentally apologizes when she bumps into inanimate objects.