In an effort to read more diversely across genre, geography, and period, I’ve started making myself monthly reading syllabi including at least one work in translation, one non-fiction, and one classic (I loosely define ‘classic’ as anything that’s been canonized in the popular imagination, usually at least three decades old).

I went off course in February and didn’t manage to get to my non-fiction pick, Slouching Towards Bethlehem by Joan Didion. As much as I appreciate having a pre-planned reading list, I’m also a big mood reader, and Didion just wasn’t calling to me (maybe it was all the noise around the forthcoming publication of her journals). Instead, I picked up The Friend by Sigrid Nunez, which I finished in a flash.

Anyway, here are my thoughts on the five books I read in February.

The Friend by Sigrid Nunez / Contemporary. Let’s start here, since I just brought it up. I highly recommend this novel if you like books about writers and writing. You’ll also enjoy this if you liked Bluets by Maggie Nelson, whose organized stream-of-consciousness, bite-sized contemplations on art, philosophy, and morality, and striking sensitivity show up copiously in these pages.

The novel follows a woman who unexpectedly loses her friend to suicide. She is entrusted with the care of his gigantic dog, whom she becomes gradually devoted to. The dog is an obvious stand-in for her friend, but soon it grows to mean much more than that.

This book wasn’t exactly what I was expecting. I thought it was going to be primarily about her relationship with this dog, and in many ways it is, but it’s also largely interested in the question of the changing relationship culture has with the figure of the writer and literature. The narrator and her friend are/were both writers; in fact, he was her professor. Through writing, the narrator attempts to tell the story of his death, which had more to do with writing than it did anything else. It’s a beautiful and curious novel.

Rejection by Tony Tulathimutte / New release. What everyone else is saying is true: it’s batshit. Gross. Shameless (which is good, because it’s a book about shame). Funny. Cringe. Simultaneously on the nose and spot on. The word bathos came to me while reading. Even though the stories only ever deal with the pathetic, the stylish hardcover packaging, plus the marketing weight of its major publishers on both sides of the Atlantic, contributes to a pleasurable dissonance between what we expect from a book like this (a decent story that nods at its buzzy blurbs —“profound”, “incandescent,” “genius”1) and what we get (10+ pages of a very disturbed man’s very disturbed sexual fantasies, transcripts of the most annoying group chat you’ve ever read, reddit copypastas, memes seven degrees removed from its original format, manifestos of the sickeningly online).

Tulathimutte’s achievement is that he does indeed nudge the profound out from the totally absurd and radically disgusting. Unlike many novels concerned with the form and content of the Internet, here, being unmannered and extremely online is not the point, but the vehicle through which he makes his larger point, which seems to be that everything that underpins a functioning society (or at least gave the impression of one)—that is to say language, morals, communication, means of labor, and modes of justice—is being perverted and thwarted beyond our control, and the consequences this has on the individual psyche and, as follows, on romantic and sexual and platonic relationships, can be immensely and irreparably harmful.

Anyway, do I recommend? What the hell, sure.

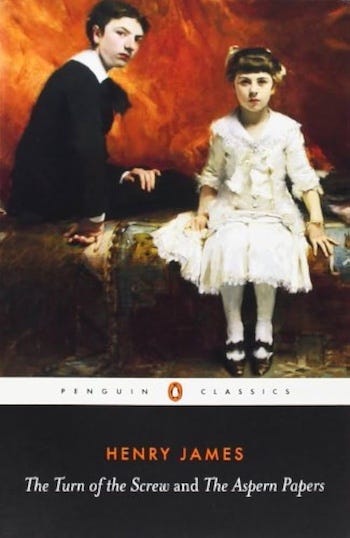

The Turn of the Screw & The Aspern Papers by Henry James / Classic. These are two roaming, obsessive stories that I took my time with. It’s easy to get lost in James’s prose. You can do it in a single sentence, and then again in the following one, over and over.

I adored the premise of The Aspern Papers. We follow the narrator, a devoted scholar of the late poet Jeffrey Aspern, as he grifts his way into the mansion of one of Aspern’s past lovers and muses. She’s rumored to have a load of never-before-seen correspondences from him, and he’ll stop at nothing to get them. I appreciated this peculiar angle of obsession: that you could be so desperately devoted to the subject of your work, who is also a real person, and justify your transgressions in the name of art. It’s great. Very suspenseful and calculated and thrilling, with a scene that made me gasp out loud.

The Turn of the Screw is one of James’s more famous works. It’s about a governess who becomes convinced that the house is haunted, full of evil spirits intent on possessing and destroying the children. She worships these children, it’s weird. Tension builds. Phantoms appear that only she can see. Or can others see them, too?? The Turn of the Screw is a more traditional suspense, full of perfectly crafted scenes that balance tension and catharsis masterfully, but I preferred The Aspern Papers.

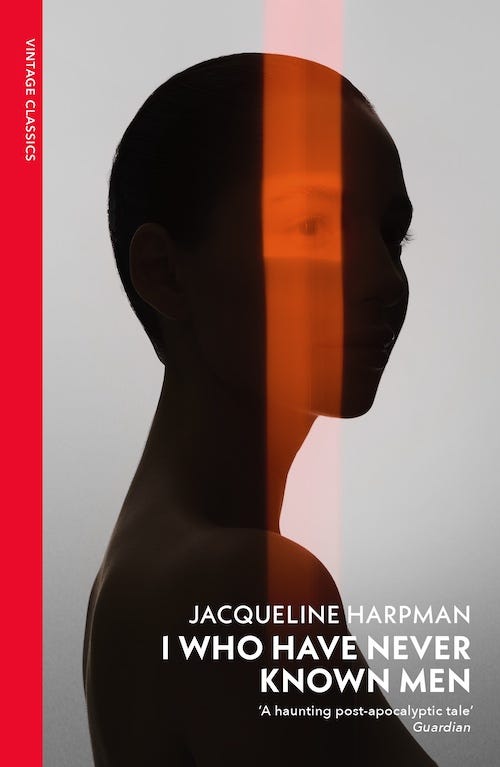

I Who Have Never Known Men by Jacqueline Hartman, translated by Ros Schwartz / Translation. I did a long-form review on this. If I had expectations going into this book, I let them all go by the second page. I knew that the story would take me places I could never predict, questions I had might never be answered, and I was glad for it. It’s the worst to read with expectations. A great book strips you of that early on.

The book is about a group of 40 women trapped in underground bunkers manned by unspeaking male guards. They have no idea why they’re there, they’ve all basically forgotten their past lives. One of them is a young girl, who is there by mistake. Because she has no memory of a normal life, she feels uniquely alone. But she is the key to their escape, and their survival, in a strange new world.

This novel takes its thought experiment to the nth degree, asking what lies at the bottom of our humanity when we are removed from everything we believe makes a life worth living: love, culture, knowledge. It is not, to me, a particularly probing novel, it’s almost passive in the face of enigma. But that’s what makes it so good. You discover the answers—if there are any—yourself. I have so much to say about it, and I have in my long-form review.

The Book of Goose by Yiyun Li / Contemporary. This novel is like if the dark and electrifying friendship of the Neapolitan Novels met the eerie finishing school of Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go, plus a streak of the smarting psychological angst of The Catcher in the Rye. We follow two best friends, Agnes and Fabienne, children in a poor backwater farming village in France. Fabienne is enigmatic, shrewd, and wickedly imaginative, and Agnes is just happy to play along with Fabienne’s experiments. Fabienne hatches a plan for the both of them to write a novel, and what follows sends Agnes on a trajectory of sudden fame and fortune.

Despite all the comparisons I made earlier, I found this book to be entirely unique. The narration is intriguing—Agnes is that rare protagonist who seems to be without motivation, desire, or ambition. But is it that she doesn’t have any, or that she’s just unaware of them? Or, is she aware, but keeping them to herself? This is a book about the vivid life of childhood, the impossibility of holding onto that world, and the disappointments and compromises of growing up. It’s about two girls who would do anything to stay in their own shared world forever.

On the syllabus for March:

James by Percival Everett (Contemporary)—I’ve actually just finished this! The pages fly by. I enjoyed the beginning, but really only felt sucked-in towards the end. More thoughts to come.

Orlando by Virginia Woolf (Classic)—My dear friends Tessa and Michael gifted this to me for my birthday. It’s one of Tess’s favorite books, and I’m so excited to read. To the Lighthouse is one of my favorite classics, and I’m looking forward to reading Woolf’s writing before she embraced the free indirect discourse of her later works.

The Safe Keep by Yael van der Wouden (Translation)—My friend Níamh recommended this, and it was just longlisted for the Women’s Prize!

American Bulk: Essays on Excess by Emily Mester (Non-fiction)—Overconsumption has become a central concern for most people talking and writing and interacting with the world today, particularly Americans, who consume the most. I’m interested in reading this book’s take on consumption, which reportedly takes an “empathetic, curious approach.”

Good Girl by Aria Aber (Contemporary)—I’ve heard great things.

Martyr! By Kaveh Akbar (Contemporary)—I really must read this now, it’s getting embarrassing.

Thank you for reading!

If you read, loved, or hated any of the above, please let me know. I love hearing your thoughts.

Words also used to describe the 2024 Booker Prize winner Orbital by Samantha Harvey, which I only bring up because I think if one of the characters from Orbital met one of the characters from Rejection, both their lives would be irreversibly changed for the worse.

Re Rejection, exactly. Exactly. Also I am now more excited to get my hands on The Books of Goose!

So excited for your thoughts on Good Girl—she’s one of a kind!